Racial Discrepancies in Kidney Disease

“While Black people make up about 12% of the U.S. population, they comprise 35% of Americans with kidney failure.” (The New York Times) “They are 3 times as likely to have kidney failure compared to White Americans.” (Kidney.org)

What causes these statistics? According to the New York Times, it’s a mix of social, economic, and genetic factors.

One gene variant, APOL1, is responsible for the genetic predisposition to kidney disease. Having two copies of this variant is prevalent in people of sub-Saharan descent, and it’s the main contributor to kidney disease. The variants make bodies resistant to efforts taken to moderate one’s blood pressure, a significant risk factor of kidney disease.

Dr. Olabisi, a kidney specialist at Duke University, advises against attributing all racial disparities of kidney disease to genetics. To do so would be to ignore the drastic effects of social and economic inequalities that lead to these jarring statistics.

Identifying the Gene Variant

About a decade ago, Harvard researchers began looking for the cause of kidney disease. They found that the APOL1 gene, which normally destroys harmful protozoa, had variants that intensified the function of the gene, making it detrimental to the body.

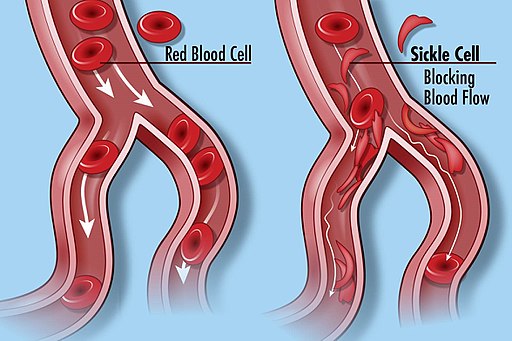

These variants evolved in people of Sub-Saharan descent because they originally protected against African sleeping sickness. There is another type of variant that averts malaria but can cause sickle cell disease. Similarly, the APOL1 variant protects against one disease, but possibly causes another.

As we learned in class, sickle cell anemia is rooted in a difference of amino acids in the primary structure of the hemoglobin of red blood cells. In position 6 of the structure, there should be glutamic acid. However, there is valine, causing the protein to fold oddly in its tertiary structures. In its quaternary structure the cells don’t react with each other as they should. As a result, he cell creates a “sickle” shape, which cannot transfer oxygen through it as successfully as the round shape.

Researchers have delved into numerous hypotheses over the year. They considered using medications to block the gene’s variants from harming the body. To find out if APOL1 was required for the kidneys to function, they consulted an Indian farmer whose kidneys functioned properly even though he didn’t have the APOL1 gene. They created a drug, and while the the dose still has to be adjusted, it’s on its way to being successful.

Semantics of Genetic Predispositions

The topic of genetic predispositions raises concerns among academics about the rhetoric that we use to describe people who are affected by the APOL1 gene variants.

Many people of different ethnicities and races have certain genetic predispositions to diseases. For example, Ashkenazi Jews have genetic predispositions to diseases such as Gaucher disease, which affects the spleen and liver, and African Americans people are more likely to have sickle cell disease.

Professor of biological sciences at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University warns against harmful rhetoric when he says, “We don’t want to fall into the myth of the genetically sick African.” I agree with his statement

It is scientifically accurate that different ethnicities have genetic predispositions to certain diseases. However, acknowledging that can be a slippery slope, especially when you consider that the most commonly known genetic predispositions effects marginalized members of society. This rhetoric partially absolves societal leaders (scientists, public servants) of effecting change in implementing preventative measures, such as improving healthcare. This rhetoric can easily slip into having Social Darwinist undertones that portray marginalized groups as genetically inferior. Do you think awareness of the language we use is important in academic spaces? Please answer in the comments if you have an opinion on this.

Ongoing Research

On another note, two twin brothers’ experiences helped further researchers’ understanding of the variants. They were asked to be part of a study that tested an arthritic drug on Black Americans to see if it could cure kidney disease. They tested positive for the APOL1 variants, which came to explain one of their kidney failures.

Researchers believe that the APOL1 variants are harmful when there are secondary factors involved, such as an antiviral response to lupus like interferon.

Dr. Olabisi’s study is pending, but in the meantime, Vertex, a drug company, wants to conduct its own research. There’s only one problem: scientists haven’t agreed on how the variants cause kidney disease, so it is unclear what a new drug should obstruct. Vertex, though, has still had some success.

They predicted that “the variants spurred APOL1 proteins to punch holes… in kidney cells” (The New York Times)

After testing on animals that were given the APOL1 variants, they found a drug that worked by identifying that it eliminated 47.6% of protein in urine, which points to improved kidney function. This is a significant step the ongoing research of trying to determine how to treat kidney disease.

In Dr. In Olabisi’s study, he plans to test 5,000 members of his community for kidney disease and the APOL1 variants, and then prescribe them with the drug used for arthritis.

These scientists and doctors are optimistic about the future of their research, and therefore, the future of kidney disease treatment and prevention, especially as it pertains to those disproportionately affected.

Leave a Reply