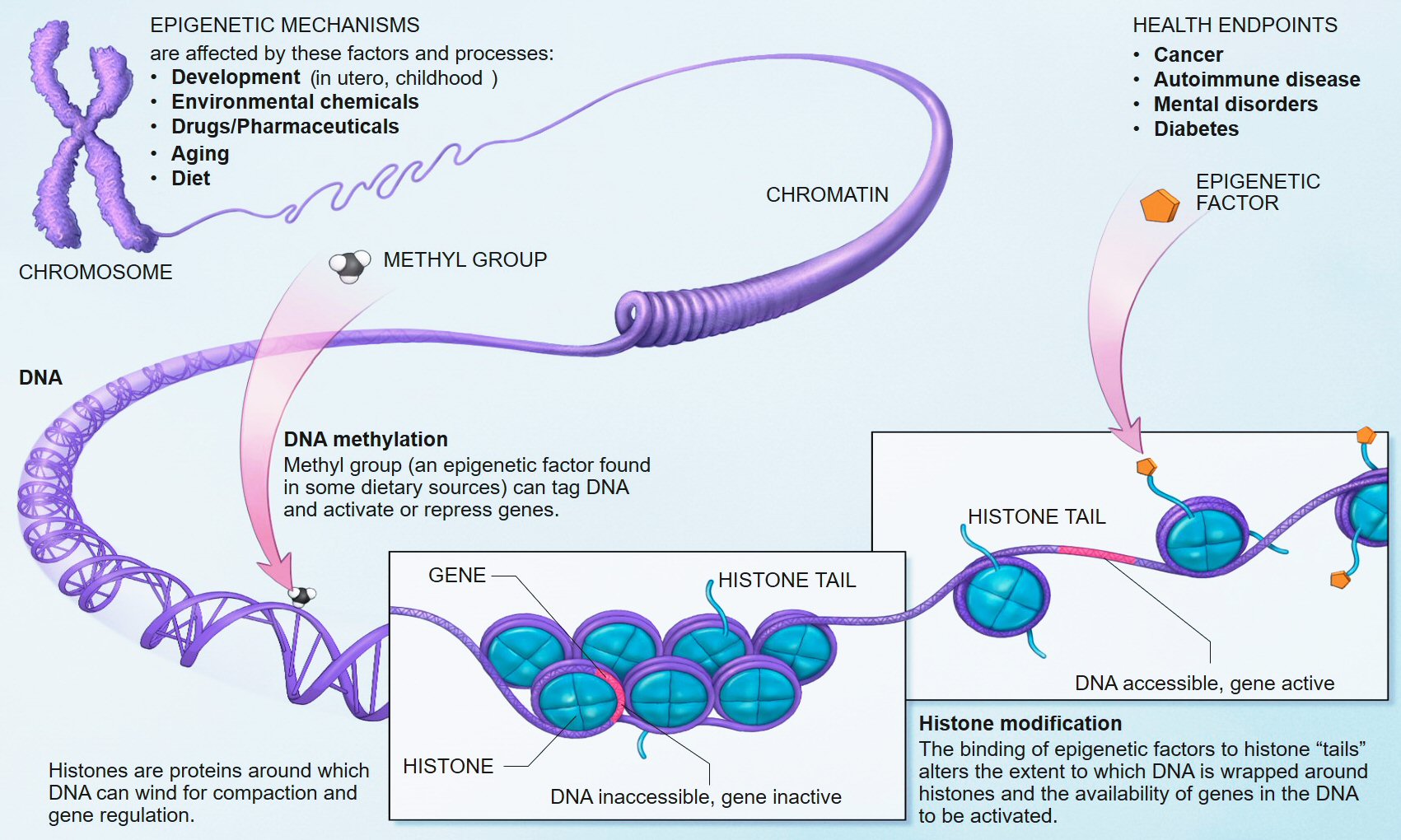

Professor Marcus Pembrey of the University College of London transcribes the complexity of epigenetics into an understandable definition, simply put as “a change in our genetic activity without changing our genetic code.” The study of “epigenetic/transgenerational inheritance” has been a field of increasing popularity within the last decade, as studies and further research are beginning to show evidence of lifestyle stresses carrying over in the genome of each generation. Now, this is not to say that our grandparents way of living changed our DNA coding but rather potentially altered the way certain genetic information is or is not expressed.

To further explore the possibility of epigenetic inheritance, a laboratory in Boston conducted an experiment on three generations of mice. A pregnant mouse was ill-fed in the late stages of pregnancy and as expected the offspring were born relatively small and later in life developed diabetes. However, the F2 generation experienced a high risk of acquiring diabetes, despite being well nourished. Another study on mice showed similar results; after a father was artificially taught to fear a particular smell, the offspring of that mouse also demonstrated a fear to the same smell.

Although the excitement over the groundbreaking research of epigenetics seems promising, researchers are still working to compile a stronger foundation of evidence to prove that this phenomena actually occurs in mammals. Professor Azim Surani of the University of Cambridge fully supports the idea of epigenetic inheritance in plants and worms, but has yet to commit to the same notion in mammals, as their biological processes differ greatly.

Leave a Reply