Throughout your life, I bet you have heard hundreds of people mention the words cancer and chemotherapy, but have you ever wondered what this treatment does inside your body? Chemotherapy is a treatment method for cancer that involves the use of powerful drugs to kill cancer cells or stop them from growing and dividing. These drugs can be administered orally, intravenously, or through other routes and may cause various side effects due to their impact on rapidly dividing cells throughout the body. Doctors have not yet found a way to target only cancer cells. This means that chemo will attack all rapidly dividing cells including hair, the digestive system, and more. Finally, a recent study has found that chemo does not work the way that doctors have thought for many years.

Before I get into the discovery, I want to explain the process of mitosis and how cancer cells can divide so rapidly. In AP bio, we learned that mitosis is a fundamental process in cell division where a single cell divides into two identical daughter cells. It consists of several stages: prophase, Prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase, followed by cytokinesis. During prophase, the chromosomes condense, the nuclear envelope breaks down, and spindle fibers form; in metaphase, the chromosomes align at the cell’s equator; in anaphase, sister chromatids separate and move towards opposite poles; finally, in telophase, new nuclei form around each set of chromosomes, completing the division process. In a normal cell, the rate of division is controlled by chemical signals from special proteins called cyclins. However, Cancer cells can divide without a signal; resulting in an extremely fast and dangerous pace of reproduction. For decades, researchers have believed that a class of drugs called microtubule poisons treat cancerous tumors by halting mitosis, or the division of cells. Now, a team of UW-Madison scientists has found that in patients, microtubule poisons don’t stop cancer cells from dividing. Instead, these drugs alter mitosis — sometimes enough to cause new cancer cells to die and the disease to regress. Beth Weaver, a professor in oncology and cell and regenerative biology found this discovery quite shocking. When hearing about this discovery she said “For decades, we all thought that the way paclitaxel works in patient tumors is by arresting them in mitosis. This is what I was taught as a graduate student. We all ‘knew’ this. In cells in a dish, labs all over the world have shown this. The problem was we were all using it at concentrations higher than those that get into the tumor.” With this discovery, scientists were inclined to see if other microtubule poisons work the same way. This led to an experiment conducted by Mark Burkard.

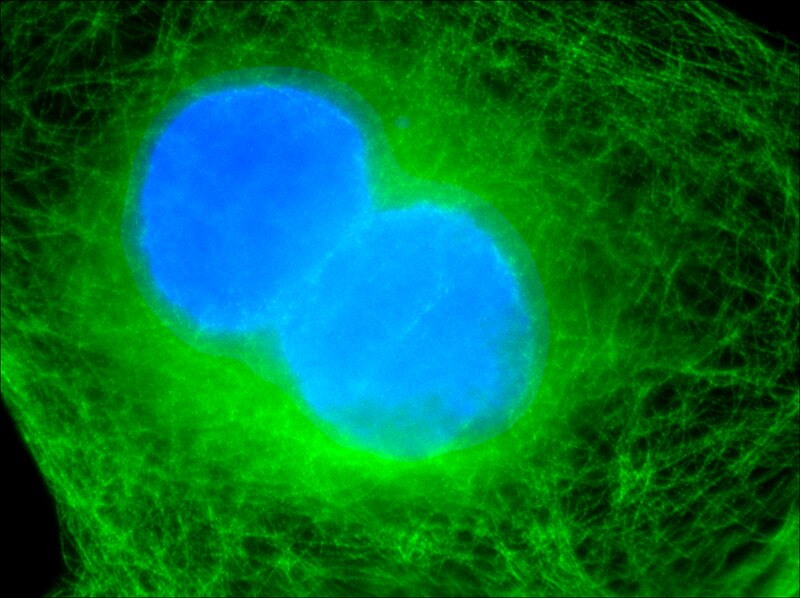

In Burkard’s experiment, he used tumor samples from breast cancer patients who had received standard anti-microtubule chemotherapy. They measured how much of the drugs made it into the tumors and studied how the tumor cells responded. They found that while the cells continued to divide after being exposed to the drug, they did so abnormally. This abnormal division can lead to tumor cell death. In normal cell division, a cell’s chromosomes are split into two identical sets. Shockingly, weaver and her colleagues found that microtubule poisons cause abnormalities that lead cells to form three, four, or even five poles during mitosis while still only creating one copy of chromosomes. This then forces the chromosomes to be pulled in more than two directions causing the genome to scramble.”So, after mitosis you have daughter cells that are no longer genetically identical and have lost chromosomes,” Weaver says. “We calculated that if a cell loses at least 20% of its DNA content, it is very likely going to die.”. This experiment was crucial to the development of cancer treatment because it was able to take the scientists off the path of attempting to completely stop mitosis and instead has them attempting to screw it up. With this new finding, what else do you think scientists have missed in some of their treatments?

Leave a Reply