Behold, have researchers found a groundbreaking method to fight tumors? Could genome-edited immune cells finally provide a way to defeat cancer?

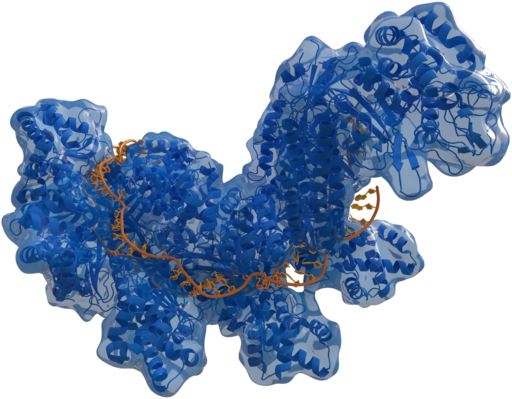

In a recent clinical trial, immune cells were modified by CRISPR gene editing to recognize mutated proteins specific to tumors. When released into the body, the cells could target and kill the specific tumor cells. This cancer research utilized gene editing and T-cell engineering.

The trial involved 16 individuals who suffered from solid tumors (including breast and colon cancer). The results were published in Nature by Heidi Ledford and then presented on November 10, 2022 in Boston, Massachusetts at The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer conference. The findings were later released in Scientific American.

According to Antoni Ribas, a co-author of the study and a cancer researcher and physician at the University of California, Los Angeles, ” It is probably the most complicated therapy ever attempted in the clinic.” He describes the process as “trying to make an army out of a participant’s own T cells.”

To begin the study, Ribas and his colleagues ran DNA sequencing on each patient’s blood sample and tumor biopsies. The goal was to identify unique mutations of the timer, but not present in the blood. Ribas notes that these mutations differ across different types of cancer, with only a few being shared. Then using algorithms, Ribas’s team predicted which mutations were the most likely to initiate a response from the T cells(a type of white blood cell that functions to notice and destroy irregular cells); however, immune systems rarely destroy cancerous tumors. With that being said, the team used CRISPR gene editing to insert designated t-cell receptors that recognized the tumor. Patients were given medication to reduce normal immune cells before the researchers infused the engineered cell.

Joseph Fraietta, who specializes in designing T-cell cancer therapies at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, describes the process as “tremendously complicated”, for some cases could take more than a year to complete in certain cases.

Each individual in the study received T cells engineered to target up to three sites, and after some time, the concentration of the engineered T cells was higher than the average T cells in the bloodstream near the tumors. A month after the treatment, five participants’ tumors had not progressed, and only 2 showed evidence of T-cell activity.

While the treatment’s effectiveness was limited, Ribas notes that a small dose of T cells was used at first and stronger doses would be proven more effective. Fraietta feels “The technology will get better and better.”

Although engineered T cells, also known as CAR T cells, were approved to treat certain blood and lymphatic cancers, CAR T cells only target proteins that are present on the surface of tumor cells, and According to Fraietta, no surface proteins have been discovered in solid tumors. Additionally, tumor cells may suppress immune responses by releasing immune-suppressing chemical signals and consuming local nutrient supplies to promote their rapid growth.

Researchers are hopeful to engineer T cells to not only recognize cancer mutations but also to become more active in the vicinity of the tumor. Potential techniques include ” removing the receptors that respond to immunosuppressive signals, or by tweaking their metabolism so that they can more easily find an energy source in the tumor environment,” as Heidi Ledford, writes in her article. With advances in CRISPR technology, researchers anticipate revolutionary ways of engineering immune cells in the next ten years.

In AP Biology this year, we learn about the Immune system. This topic is specifically related to the adaptive, or pathogen-specific, Immune response. T Lymphocytes, or T cells for short, are a part of the cell-mediated immune response where T-cells can identify, and kill infected or cancerous cells, while also preventing reinfecting.

Leave a Reply