Antibiotics as a treatment are never fun – not only are you most likely dealing with a bacterial infection, but you need to take them on a strict cycle and can be quite aggressive on your stomach. I once had to go on antibiotics for treating a sinus infection, and it didn’t quite make me feel better after taking it. So after, I went on the same antibiotic, Cefuroxime, and took a higher dose, but I was not consistent in taking it and started feeling ill. This reaction was due to the antibiotics impact on the protective bacteria in my stomach’s microbiome. I soon learned more about the effects the antibiotics had on my stomach’s microbiome, and realized the common misconception around antibiotics – that they only benefit one’s health – and how some of the symbiotic relationships with bacteria in there are essential to digestion and immune protection.

Antibiotics as a treatment are never fun – not only are you most likely dealing with a bacterial infection, but you need to take them on a strict cycle and can be quite aggressive on your stomach. I once had to go on antibiotics for treating a sinus infection, and it didn’t quite make me feel better after taking it. So after, I went on the same antibiotic, Cefuroxime, and took a higher dose, but I was not consistent in taking it and started feeling ill. This reaction was due to the antibiotics impact on the protective bacteria in my stomach’s microbiome. I soon learned more about the effects the antibiotics had on my stomach’s microbiome, and realized the common misconception around antibiotics – that they only benefit one’s health – and how some of the symbiotic relationships with bacteria in there are essential to digestion and immune protection.

Biological overview

Antibiotics have been around since 1928 and help save millions of lives each year. Once antibiotics were introduced to treat infections that were to previously kill patients, the average human life expectancy jumped by eight years. Antibiotics are used to treat against a wide variety of bacterial infections, and are considered a wonder of modern medicine. However, they can harm the helpful bacteria that live in our gut.

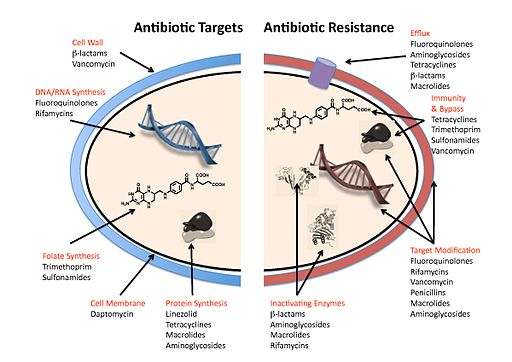

The word antibiotic means “against life”, and they work just like that – antibiotics keep bacterial cells from copying themselves and reproducing. They are designed to target bacterial infections within (or on) the body. They do this through inhibiting the various essential processes we learned in Unit 1 about a bacterial cell: RNA/DNA synthesis, cell wall synthesis, and protein synthesis. Some antibiotics are highly specialized to be effective against certain bacteria, while others, known as broad-spectrum antibiotics, can attack a wide range of bacteria, including ones that are beneficial to us. Conversely, narrow spectrum antibiotics only impact specific microbes.

The Human stomach is home to a diverse and intricate community of different microbial species- these include many viruses, bacteria, and even fungi. They are collectively referred to as the gut microbiome, and they affect our body from birth and throughout life by controlling the digestion of food, immune system, central nervous system, and other bodily processes. There are trillions of bacterial cells made of up about 1,000 different species of bacteria, each playing a different role in our bodies. It would be very difficult to live without this microbiome – they break down fiber to help produce short-chain fatty acids, which are good for gut health – they also help in controlling how our bodies respond to infection. Many antibiotics are known to inhibit the growth of a wide range of pathogenic bacteria. So, when the gut microbiome is interfered with using similar antibiotics, there is a high chance that the healthy and supportive microbes in our stomachs are targeted as well. Common side effects of collateral damage caused by antibiotics can be gastrointestinal problems or long-term health problems (such as metabolic, allergic, or immunological diseases). There is a lot of new research on the gut microbiome, some even suggesting that it impacts brain health by influencing the central nervous system. It is essential that we know more about how we can optimize its overall well-being.

New Research

Tackling the Collateral Damage to Our Health From Antibiotics

Researchers from the Maier lab EMBL Heidelberg at the University of Tübingen have substantially improved our understanding of antibiotics’ effects on gut microbiomes. They have analyzed the effects of 144 antibiotics on our most common gut microbes. The researchers determined how a given antibiotic would affect 27 different bacterial strains; they performed studies on more than 800 antibiotics.

The studies revealed that tetracyclines and macrolides – two commonly used antibiotic families – led to bacterial cell death, rather than just inhibiting reproduction. These antibiotic classes were considered to have bactericidal effects – meaning that it kills bacteria rather than just inhibiting their reproduction. The assumption that most antibiotics had only bacteriostatic effects was proven not to be true; about half of the gut microbes were killed upon being treated with several antibiotics, whereas the rest were just inhibited in their reproduction.

These results expanded existing datasets on antibiotic spectra in gut bacterial species by 75%. When certain bacteria in the gut are dead, and others are not, there can exist an reduction of microflora diversity in the microbiota composition; this concept is referred to as dysbiosis. This can result in diarrhea, or even long term consequences such as food allergies or asthma. Luckily, the Researchers at EMBL Heidelberg have suggested a new approach to mitigating the adverse effects of antibiotics on the gut microbiome. They found that it would be possible to add a particular non-antibiotic drug to mask the negative effects the antibiotics had. The Researchers used a combination of antibiotic and non-antibiotic drug on a mouse and found that it mitigated the loss of particular gut microflora in the mouse gut. When in combination with several non-antibiotic drugs, the gut microbes could be saved. Additionally, they found that the combination used to rescue the microbes did not compromise the efficacy of the antibiotic.

It has been known for a while that antibiotics were impactful on gut microbiome, but its true extent had not been studied much until recently. More time is needed to identify the optimal dosing and combinations, but the research coming from the Maier lab is very substantial as it fills in “major gaps in our understanding of which type of antibiotic affects which types of bacteria, and in what way,” said Nassos Typas, Senior Scientist at EMBL Heidelberg.

Leave a Reply