Over the past five years or so, ancestry and DNA tests have risen in popularity due to people’s desire to find out what medical conditions they are at risk for, or where their ancestors are from. The most common concern I have heard about as a result of these tests was that the companies would sell your DNA to third parties or the government (while there is a chance this could be true this will not be the focus of this article). However, the true problems are not conspiracy driven, yet they are scientifically driven and verifiably true.

Many people using these tests do not realize how these tests actually work and the wrong information they present at times. The first issue resides in the health screenings of these ancestry tests. They claim to use your ancestry to see if you are at risk for Alzheimers, certain types of cancer, Parkinson’s, or what type of body type you have. These companies are not completely lying, however the tests can omit certain things and it is no substitute for going to an actual doctor.

Everything they search for is compared to a reference population, therefore your genes are merely compared to other people who are considered healthy or unhealthy. These tests do not have access to medical history in order to look for other clinical factors that could accelerate or further exacerbate this potential condition, thus explaining why it is irresponsible to tell people they are at risk for a debilitating disease because someone with similar genetics reported developing a disease that could have resulted from his or her specific lifestyle.

The issue with self-reporting in ancestry tests also can be seen in testing for heritage. The data these companies use are based off of reference populations (many of which are self-reported especially in the early years of the tests), therefore the same person can receive different results at different times. The database is constantly changing (which isn’t necessarily only a bad thing) so if the same person takes the test three times in three different years, they are likely to get different results. If the company recently expands to selling DNA kits in a new area of the world, a person with mixed heritage from the United States can receive different results because the test population of a certain region was extremely small and unspecific before, whereas now they have more of a test population that can change “how Vietnamese you are” (or whatever region that applies to you).

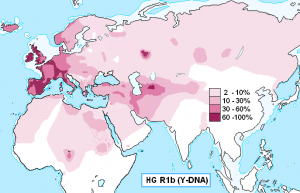

Have you ever known someone who took the DNA test and found out they were not as Greek or Russian (insert anything) as they thought they were? These results are problematic on so many levels when breaking down ancestry. The first example is that when comparing extremely similar populations, your heritage might not reflect your ancestry that the test finds. For example: modern English, Scottish, and Irish people have vastly similar results in these tests because they are very similar genetically and geographically, therefore a person can find out they are 50/50 Irish and English, however all of their known relatives can be traced back to 1870s Ireland. The person is not “less Irish than they thought”; it merely means that centuries of migration and conquering in the region of the British Isles could blend the gene pools even if this person’s family tree of the last two-hundred years can be traced back to one specific town.

Something else important to consider is that ancestry and heritage are not nearly synonymous terms. Furthermore, two twins could receive different genes from the same parents which could lead to slight changes in genetic makeup. Your sibling is not “more Swedish than you” in terms of heritage and the culture you were raised in. The sibling might receive a certain gene from your parents that you did not.

While there are a myriad of problems and hypotheticals to bring up, I will leave you with one last problem. Groups of people that live in diaspora such as Jews, Romani, and Armenians could have problems with these tests. Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe live in diaspora and have been a migratory group for centuries, leading them to mix in with various gene pools that they settle in. When an Ashkenazi Jew or Romani (who similarly lived a migratory history) takes an ancestry test, they could feel completely related to their Ashkenazi or Romani heritage, however the intermixing of people over centuries (because they settled in so many places) could come up in the test even though they feel like they have no relationship to the heritage at all. Romani people also are difficult to pinpoint to one specific region of origin which demonstrates another potential problem with the tests.

While these tests can be a fun activity to do with your friends, make sure you take the results with a grain of salt because you are not necessarily “less French than you thought”.

dannimal

Thank you for such a thought provoking article Andygen! I share yours and other commenters concerns on the subject of these so called ancestry tests. I always here the murmurings about wanting to do these tests wherever I may be and am always oddly amused by the general fixation most people have on learning secrets about themselves through their own DNA. It is certainly a fascinating subject to ponder on. On the subject on the validity of these tests: I found this great article with the headline “I Took 9 Different Commercial DNA Tests and Got 6 Different Results.” I think that says it all. Extra revelatory was the idea brought up in the article that these tests are a misuse of the genetics science they are based on as it “is used to figure out how large groups of people moved and mixed over time. And it’s good for that purpose. But figuring out whether 3 to 13 percent of my ancestors came from the Iberian Peninsula or Italy isn’t part of that project.” If you’d like to read more from the article this is the link: https://www.livescience.com/63997-dna-ancestry-test-results-explained.html. I truly wonder how our understanding of these tests will develop as the novelty of them starts to wear off.

metalibolism

This is very interesting. Although there are issues with giving false or misleading information, genetic testing can be helpful in giving people information they don’t have access to. It certainly shouldn’t take the place of a doctor’s opinion or test if there is a known disease that runs in your family, but they never claim to do so. The results are only meant to “help to make decisions about lifestyle choices or to inform discussions with a health care professional,” according to https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/04/07/522897473/fda-approves-marketing-of-consumer-genetic-tests-for-some-conditions. Regarding heritage and ethnicity, although it can be inaccurate, it is still helpful in giving people a general sense of their genetic makeup. If you already have an expectation from your parents of your heritage and ethnicity, then the unclear results from genetic testing might not be necessary.

Branchiolon

Great job Andygen! The fact that most of these ancestry services use algorithms that use variable reference populations was very useful information to share before someone decides to confide completely in an ancestry test. Interestingly, an article by Live Science https://www.livescience.com/62690-how-dna-ancestry-23andme-tests-work.html mentions how the methods that have been by these ancestry companies is often based in ancient techniques, such as “Mitochondrial Eve”, the supposed ancestor of all human beings. Perhaps the accuracy of these long used methods could complicate the ethics of these ancestry tests mentioned by Widgeon.

Brandon

Great job Andygen! The fact that most of these ancestry services use algorithms that use variable reference populations was very useful information to share before someone decides to confide completely in an ancestry test. Interestingly, an article by Live Science https://www.livescience.com/62690-how-dna-ancestry-23andme-tests-work.html mentions how the methods that have been by these ancestry companies is often based in ancient techniques, such as “Mitochondrial Eve”, the supposed ancestor of all human beings. Perhaps the accuracy of these long used methods could complicate the ethics of these ancestry tests mentioned by Widgeon.

Widgeon

Very interesting article Andygen. I completely agree that these tests are not completely accurate. There is definitely a harm if these tests give false information. For example, if I am using this test to see if I am at a heightened risk of getting cancer and the test results say that I am not, I will not be taking the necessary precautions to make sure that I do not become ill. There definitely are some benefits to taking this test, One, getting a general idea of your heritage can be very important for some people. Also, if your DNA is now in a database, in crime scenes and investigations, your DNA could be very useful. If ancestry.com is not correct in their results, is that morally wrong to give the person false information about their heritage? Here is an article that connects to your blog post: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/16/5-biggest-risks-of-sharing-dna-with-consumer-genetic-testing-companies.html

This article discusses all of the issues with DNA testing and how it can be potentially harmful to you.

brianaryfission

While the inaccuracies of ancestry.com are evident, the use of DNA in police investigations is super interesting in terms of bio-ethics. DNA has long been a source of contention around the privacy of each person, and this article furthers the discussion around access to this information: https://www.theroot.com/police-obtain-warrant-for-ancestry-com-dna-database-1841451890 . I wonder if the inaccuracies of tracing back the lineage of a person will serve to make this method less useful than it may seem, as well as not exactly ethical.

jessophagus

I agree with Andygen in that ancestry tests are less accurate than they seem and have potential areas of conflict. In addition to the issues mentioned, the algorithm that 23andme standardly uses has relatively low confidence intervals. This is a statistics principle that measures the accuracy of data. For example, a 50% confidence interval indicates someone can be at least 50% sure a result is accurate. As the confidence intervals increases in value, 23andme can less accurately assign ethnicities and states them as broad categories like “Broadly East Asian.” This is problematic because recipients of the test may forget to alter the confidence interval, either not understanding its significance or unaware of its existence. If that same person is told he or she is of one ethnicity in a low confidence interval, that gives a false sentiment of understanding since, in reality, they can only be sure they are from a large, nonspecific region.

Source: https://customercare.23andme.com/hc/en-us/articles/115004491928-Using-the-Advanced-Features-in-DNA-Ancestry-Composition