Recently, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and his collaborators at the University of California, San Francisco have discovered a way to repurpose CRISPR, a gene-editing tool, to develop new antibiotics.

What does this mean?

It is known that many disease-causing pathogens are resistant to current antibiotics. This new technique, Mobile-CRISPRi, is helping to change that. Mobile-CRISPRi allows scientists to “screen for antibiotic function in a wide range of pathogenic bacteria.” Scientists used of bacterial sex to transfer Mobile-CRISPRi from laboratory strains into any diverse bacteria. This easily transferred technique will now allow scientists to to study any bacteria that cause disease or help one’s health.

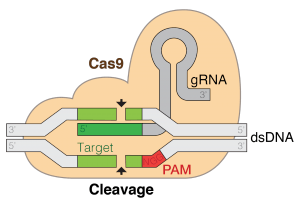

To break it down, Mobile-CRISPRi “reduces the production of protein, from targeted genes, allowing researchers to identify how antibiotics inhibit the growth of pathogens.” This will allow researchers to more thoroughly understand different bacterias’ resistance to current antibiotics.

Unlike CRISPR, which can split DNA into two halves, CRISPRi is a defanged form that is unable to cut DNA. Instead, it stays on top of the DNA, blocking other proteins from being able to turn on a specific gene.

Why is this important?

It has been proved that a decrease in the amount of protein targeted by an antibiotic will make bacteria become more sensitive to lower amounts of that same antibiotic. This evidence association between “gene and drug” has allowed scientists to “screen thousands of genes at a time,” as they try to gain more knowledge about the mechanisms of how antibiotics work in organisms to improve those on the market now.

In order to study how antibiotics directly work in pathogens, researchers needed to make this CRISPRi mobile, or easily transferred onto different bacterias. There were two tests done to test CRISPRi’s mobility using conjugation. One involving a transfer of CRISPRi to the pathogens Pseudomonas, Salmonella, Staphylococcus, Listeria, and others, and another involving the bacteria that grows on cheese.

Science Daily describes the “landscapes of microbes cheese creates as it ages.” A bacteria called “Vibrio casei” was found on a French cheese in a lab back in 2010. With bacteria that have been taken out of their environment, it is hard to manipulate and study said pathogen’s genes, like “Vibrio casei.”

However, the mobile-CRISPRi was able to easily transfer onto the strain of Vibrio casei that was discovered back in 2010. This has given scientists a new way of understanding how bacteria colonizes and ages cheese.

Peters, the head researcher of mobile-CRISPRi is generous enough to offer this system to other scientists who would like to study other germs. With this technology being available to others, scientists could potentially see first-hand how antibiotics work in pathogens, and use that information to improve those that currently exist, hopefully getting rid of these bacterias like pseudomonas, or listeria before they kill the human they are inside of.

Leave a Reply